Statues also considered art can be seen as a way to celebrate, remember, and tell the stories of culturally or historically significant people. However, they are marks of history or recognition of good deeds and bad – or both.

Our relationship to a statue normalizes the past for better or worse, in doing so their (statues or monuments) power ebbs and flows.

We live in uncertain times, but all around us, historical forces that have always shaped our lives have now become visible.

This is the blindness of everyday life.

Facts matter and the protests are, at the bottom, about facts – the historical truth of colonialism, slavery, and patriarchy, and the contemporary truth of the people they still marginalize.

Some argue that statues are an important ‘window’ into the past as they reflect who – and what – was important at the time they were built.

I can remember when Nelson was blown sky-high by the IRA in 1966 followed by Wellington.

Fast-forward to 2022.

The wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria have displaced nearly 20 million people, part of the largest refugee crisis in modern history. The top 1% of people now own half of the global wealth, while the bottom 70% account for less than 3%.

The past few years have seen a recession, with the steady breakdown of international norms, the rise of illiberal democracy and re-entrenchment of authoritarian regimes, and the emergence of rightwing populism in the west, leading to the self-inflicted wounds of Brexit and the Trump presidency.

Meanwhile, the world faces a new existential crisis: climate change. The impact of decades of unchecked growth is now undeniable, with rising temperatures and quickening cycles of natural disasters that threaten new calamities every day.

Suddenly life feels overdetermined, shaped by forces larger than any individual, community, or nation.

Little by little, we begin to connect the inequality of the present to the past and this is why statues, buildings, and street signs have become flashpoints because they embody the tension between two worldviews of having and not having.

Virtually all western cities are monuments to colonialism.

Either they were superimposed on earlier indigenous settlements (New York), founded to support the trade in slaves and natural resources (Cape Town), or substantially built with capital extracted from the colonies (pretty much any major European city).

Removing a few of the most egregious statues will not, as some people fear, erase the histories of these places, nor diminish the cultural heritage their residents are, for better and worse, heir to.

So what are we allowed to see, hear, and what if anything can be done?

We can modify statues to recognize historical truths and to perform a kind of apology, but that’s as far as agonism goes. Given the now impossible-to-ignore continuity between the misdeeds of the past and the conditions people face in the present, this feels insufficient.

Erasing history and arguing that people in the past can’t be judged by attitudes today – statues should be preserved because they teach people about the past, even if it is seen as unpleasant now.

I am of the opinion that new plaques should be added which explain why the person is controversial, reflecting both the good and bad things they did.

Everyone agrees as society’s values change, reconciliation can’t just be about the past it must be forward-looking by reflecting a country’s diverse population which were and still are traditionally focused on white men.

Beliefs or views held by the figures when they were alive will not be erased by removing statues to museums.

The question now is.

Does the plaque justify that the statue should stay in place?

The statues were built to honor and enforce white supremacist views, and the intent or damaging effect has not been erased by time.

Monuments to men who advocated cruelty and barbarism of any kind to achieve are a grotesque affront to moderne the day cultures of mixed societies.

Their statues pay homage to hate, not heritage.

We don’t want to leave this so that people looking back in 50 years will say: you know, they took the statues down, why didn’t they do something about racism?”

Finally here are a few examples to chew over.

The UK The Foreign Office has a painting. The picture shows the racial world of Britannia is ordered.

The superior Anglo-Saxons show their naked bodies, but cover their loins, subordinate races, such as Indian and Arab, are fully clothed, and the ‘least’ of races, the African, is still a naked infant.

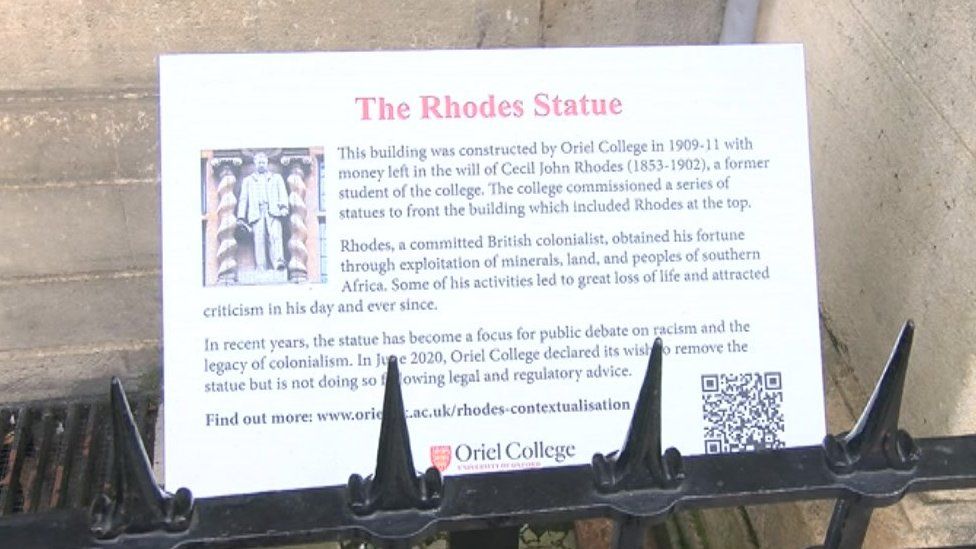

Here we have a racial meta-narrative clearly imprinted on the body.  British imperialist Cecil Rhodes statue is above the entrance to Oriel College, on Oxford High Street.

British imperialist Cecil Rhodes statue is above the entrance to Oriel College, on Oxford High Street.

Is his non-removal an “act of institutional racism”?

He was a slave trader in the 17th century (the 1600s) and part of a group called the Royal African Company, which transported about 80,000 men, women, and children as slaves from Africa to the Americas.

The Statue now has the below plaque.

The plaque directs readers to the college’s website and an article entitled “Contextualisation of the Rhodes Legacy”.

Edward Colston: Slave trader.

He was a slave trader in the 17th century (the 1600s) and part of a group called the Royal African Company, which transported about 80,000 men, women, and children as slaves from Africa to the Americas.

It made him very rich and when he died in 1721, he left a lot of money to charities and good causes.

We cannot weigh morally significant achievements against serious wrongdoing in order to justify public statutes of wrongdoers. In my view governments have a duty to condemn and repudiate serious wrongdoing that is incompatible with retaining public statues of historical figures who perpetrated serious rights violations.

No comments:

Post a Comment